Bài viết tiếng Việt: https://khoahocphattrien.vn/kham-pha/silvia-federici-va-phong-trao-doi-tien-cong-cho-viec-nha/20221021104210758p1c879.htm

Silvia Federici and the demand for “Wages for Housework” – Silvia Federici và phong trào đòi tiền công cho việc nhà

Mèo Mju kêu meo meo

Dang-Thanh Nguyen

Vietnamese version of this book review “Silvia Federici và phong trào đòi tiền công cho việc nhà” (on Wages against Housework, 1975, ISBN: 978-095-02-7029-6) was published in Khoa học và Phát triển [Science and Development: the weekly newspaper of Vietnam Ministry of Science and Technology of Vietnam ] no. 42 (1210), October 20, 2022, issues on Vietnam women’s day, pp. 19-20.

Silvia Federici, an Italian activist and researcher, co-launched a campaign in the 1970s against the social division of labour that forces women to do unpaid housework, which she considered a fundamental aspect of the process of extending exploitation to the whole of society, even in seemingly non-capitalist relationships.

She was born in Italy in 1942, at an epoch when women went to work very little. Her mother, without exception, was a full-time and unpaid housewife. Living close to her mother, Silvia Federici was educated about the status of housewife in a post-fascist and capitalist society (and was subjected to the economic scrutiny of the World War II winning governments). This status – she was awarded during her teenager – was worse than death. To go against that fate, she used her education. She was trained as a philosopher, receiving a Bachelor’s degree from the University of Bologna in 1965, then a Master’s degree from SUNY Buffalo State College, New York, USA, in 1970.

In New York, she “went through a life change”, – as she wrote in a letter to me from August 2022. Silvia Federici studied Karl Marx, the premise to becoming a scholar following Karl Marx’s pattern: refusing to just observe the world, like German idealist tradition, but attempting to change it. Her vita nova began at the age of 30 when she co-founded the Wages for Housework campaign (WFH). The campaign was formed in 1972 from a meeting in Padua, Italy, of a group of female scholars and activists to discuss a new strategy for social movements for women (at that time, the proportion of women working in the Western nations was still low).

Since 1940, the United Kingdom government has given women who are raising children a family allowance, which does not cut into their husband’s wages. UK government, however, after World War II, under pressure from economic recovery and development, gradually cut off that allowance – the main source of income for women to maintain their independence from their husbands. In the United States, there was an allowance for families with dependent children, also the main income of housewives. This allowance began to be reduced in the early 1970s, which created the Welfare Mothers movement. The most revolutionary part of this movement was black mothers and wives, who were subject to intersectional oppression: race and economics.

WFH’s response to the demands of social reality was to identify the main object of the movement and also the most revolutionary element in the struggle towards socialism: housewives. Although many socialist authors, such as the Russian writer Maxim Gorky (1868 – 1936), with his novel The Mother, printed in 1906, respected mothers and housewives but did not consider them as an element of socialist revolution.

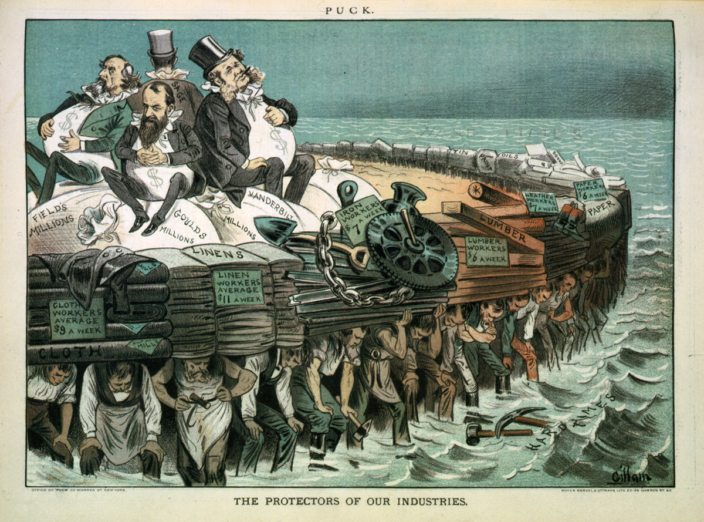

The theoretical premise of WFH is a 1971 paper by co-founder Mariarosa Dalla Costa (1943), Women and the Subversion of Community, which explains resistance to the status of the wife and the housewife (that Silvia Federici intuited from her teenage years). Mariarosa Dalla Costa positions the naturalization of the social division of labour that has forced women to do unpaid housework as the basis of primitive capital accumulation in capitalist societies. That is, the traditional exploitation in the factory has extended to the whole of society in relations that seem to be non-capitalist.

Follow that theorical premise, Silvia Federici’s most famous work, which is also a classic of housework research, Wages against Housework, opens with these words: “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work./They call it frigidity. We call it absenteeism./Every miscarriage is a work accident.”. She started writing it in 1974, gave it a wide public speaking, and printed it as an 8-page pamphlet, in format 14 x 22 cm, at the publishing house supported the campaign, Falling Wall Press in 1975.

Silvia Federici explains the contrast between the paid work of working people and the unpaid housework of the wives and stay-at-home mothers in the capitalist societies in which she lives. Wages are the recognition that a worker has worked, thus acknowledging that a person is worthy of being a member of society. The number of unpaid workers – of which housewives are a part – are considered unemployed, unworthy of becoming members of society. The only way for them to be recognized is to enter the labour-power market. But even if women work in an office or a factory, a second job, their housework is not considered work.

Housewives and mothers feel the exhaustion of their mental and physical health while working house – no less than workers in factories or offices – so they protested. However, their protest was torn apart and privatized, becoming quarrels between husband and wife in the kitchen or in bed, which “all society agrees to ridicule”. They are devalued labour-power, therefore dignified, considered only as “nagging bitches”. The struggle of housewives and mothers in Britain and the United States in the 1970s, while not demanding wages but demanding social welfare, was, for Silvia Federici and WFH, a reality that could create possibilities unite women under one short-term goal: “wages for housework”.

Demanding wages for housework, which is against the naturalization of the social division of labour, places women in unpaid household chores. This requirement, at the same time, forces society to recognize that housework is also a job, thus recognizing socially and economically the role of housewives. From the seemingly trivial and obvious things in the kitchen and bed in every home, Silvia Federici go to establishing a political position, questioning social services, and returning to the story of housework. This sequence of phenomenological presentations itself shows that housework is an essential and constant activity of human life and that social change necessarily begins with housework.

The revolution based on a radical change in women’s housework is, for Silvia Federici, “revolution at point zero”. Thus, Silvia Federici’s Wages Against Housework is considered as a manifesto of working-class women, born 127 years after the manifesto of the working class, Marx and Engels’ Communist Manifesto (1848).

The practical demand for wages of housework until the late 1970s were unsuccessful. Governments do not accept to pay wages for housework and cut family allowance to a dramatic extent. The 1970s in the UK and the US, the two most representative capitalist governments and societies, criminalized women – mostly black women – who wanted welfare and wages for housework. That black women are thus portrayed as thieves, couch potatoes, and ignorant. In 1977, the WFH campaign ended.

But Silvia Federici did not give up. She continued to be politically active and expanded her research to other aspects around the issue of social reproduction, including women’s housework.